Soprano Carrie Shaw opens up about her new staging of Pierrot Lunaire, to be performed at Dal Niente’s June 2 Party.

The Body of the State: Snippets

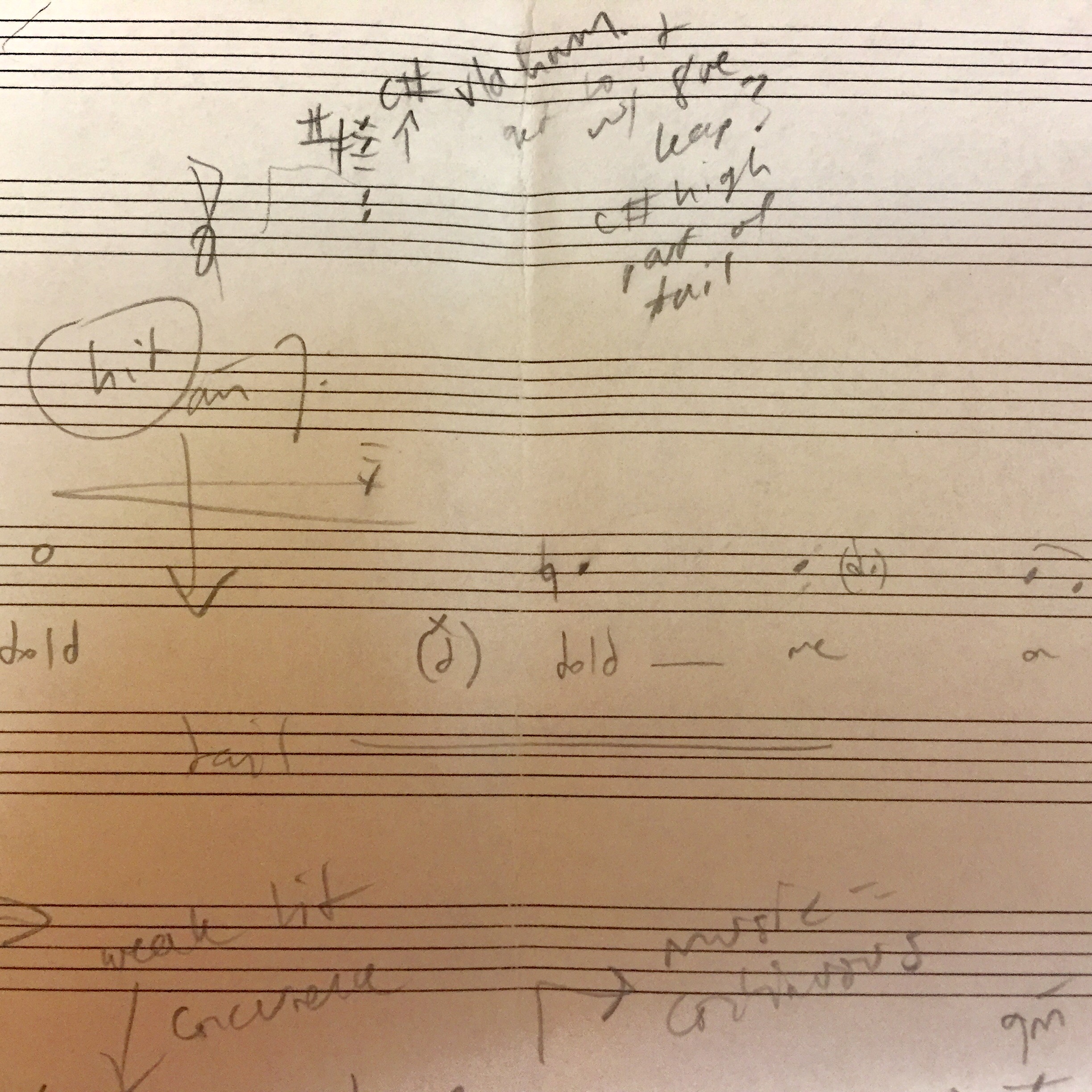

Eliza Brown's The Body of the State premieres on October 20 at the EDGE theater. Here, the composer shares a handwritten sketch of part of Scene III and an audio clip from her recording session at the Indiana Women's prison.

Handwritten manuscript from The Body of the State, Scene 3

Harp, Dancers, Piano: Interview with Tomás Gueglio and Ben Melsky

We sat down with composer Tomás Gueglio and harpist Ben Melsky to talk a bit about Tomás’s new work Proa and working with dancers from Delfos Danza Contemporánea.

Old New Music: Pierrot Lunaire and the Chocolate Factory

Interview with Eliza Brown: Epistemic Injustice, Juana of Castile, and the Women of Indiana Women's Prison

“My bondage shall not / keep my story bound

”

In this interview, EDN violist Ammie Brod sits down with composer Eliza Brown to ask some questions about The Body of the State, Brown's new monodramatic work that Ensemble Dal Niente will premiere as part of its STAGED series in 2017-2018.

Q: First off, can you tell us a little about the history behind your monodrama?

A: The Body of the State is a monodrama for soprano and ensemble about Juana of Castile. Juana, born in 1479, was the daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella, the rulers of what is now Spain. At 16, she was married to Philip of Burgundy, who soon proved abusive and unfaithful, denying Juana power in the household and locking her in her chambers as punishment.

In 1506, both Isabella and Philip died, leaving Juana, at age 27, sole heir to the Castilian throne. She found herself locked in a battle for power with her own father, who strong-armed her into signing away her governing rights, leaving her queen in name only. Rumors of her insanity were spread by her political enemies, and her father had her confined to a house in Tordesillas, surrounded by servants and priests whom he paid to lie to her, control her, and interrogate the legitimacy of her faith

Q: That’s very . . . operatic, isn’t it?

A: It is, and that’s part of what got me interested in Juana’s story. I was initially drawn to this as a “hidden narrative” of women’s history, the dark origin story of the Hapsburg empire. But I also appreciated its operatic-ness: the scale of its drama, its emotionally fraught scenarios, the family power plays that affect thousands of people, and as a composer I was interested in the opportunity to allude to and subvert the operatic trope of the madwoman.

Q: Has the focus of your interest changed as you’ve delved deeper into the story?

A: It has, for a number of reasons. As this project developed over the last few years, Juana’s story came to feel more and more relevant to the modern world. Women are still used as political pawns via arranged marriages. The stigma of mental illness is still used to discredit the voices of survivors of abuse and oppression. Educational disparities still undermine the human potential of women and girls around the globe. Incarceration is still used as a method for controlling the non-conforming and the politically threatening, and women still face intense opposition when they pursue political power. This is not only a historical story, but a human story.

Last fall I was involved in a faculty/staff reading group at DePauw University which met via videoconference with the graduate class at Indiana Women’s Prison. We read articles by philosophers and by women in the prison about the concept of “epistemic injustice.” Epistemic injustice occurs when we discount someone’s ability to be a knower, reducing that person to a knowable object. This form of injustice affects many marginalized people, including the incarcerated. As I learned about epistemic injustice from the women at IWP, I felt it perfectly described Juana’s situation. This changed my understanding of the character, and of the text and music she ought to sing.

I felt an ethical responsibility to tell the IWP scholars that their work had influenced mine, and an ethical desire to offer them a way to participate in this project as a small corrective to epistemic injustice. A number of women were interested in participating, and we scheduled a series of meetings to discuss the form that might take.

“

The body of Juana of Castile is likened unto a strikingly luminescent orb. An orb floating about the land of her people, equally tangible and intangible, equally desired and repulsed, beautiful, but hard to look at, hard to take in....In the story of power misused against her and the dilution of her own power, we see a woman who had no real possession of her body.”

Q: There are so many levels of collaboration going on in this project! Can you tell me more about the form that this specific collaboration ended up taking?

A: It was important to me to approach this particular collaboration in a way that minimized the position of power I was systemically assigned to, so at first I asked a lot of questions: how do we do this together? Initially, we discussed excerpts of a book about Juana, and then the women wrote responses to it in the formats that felt most appropriate to them. We picked through these responses together, editing and combining them into a libretto. We went through several rounds of editing, giving feedback, and then editing again.

More concretely, I wrote the libretto for the second scene before the collaboration; the librettos for the first and third scenes were written with them. We have no text actually written by Juana to work with, despite her presumed education; all we know of her life is what other people wrote about her. Much as I wanted this monodrama to subvert the operatic paradigm of the mentally unstable female, I wanted this collaboration to subvert the epistemic injustice that prisoners, including both Juana and my collaborators, experience on a daily basis.

Q: Aside from the concrete contribution of a libretto, were there other ways this collaboration shaped your piece?

A: Absolutely. The piece now includes aspects of Juana’s story and psychology that I had not prioritized. For instance, the character now mentions her children several times, and at one point mistakes someone else on stage for one of her sons. I had initially planned to leave out references to her children for the sake of theatrical simplicity, but the women thought we had to find a way to include them.

Our conversations also complicated my perception of Juana as a constant victim. My collaborators picked up on her ability to maintain small forms of resistance to injustice, even if that resistance was sometimes to her detriment. They saw her as strong, because she’s aware of the injustices in her world and resists them instead of being broken by them. Juana heroically attempted to assert her agency against all odds, despite losing battle after battle and despite the opposition of everyone around her. Her story is simultaneously tragedy and triumph.

They’ve also had a hand in the sonic world of the piece. Juana’s mental health is somewhat ambiguous in the historical record: was her mental instability innate, or imposed by circumstance? Some of the women I’ve been working with have had personal experiences with mental health that are not unlike Juana’s, and this prompted a discussion of sound and what sounds could be used as triggers for or symbols of her mental instability within the scope of the piece. Some of these--an electric guitar string being scraped while a flute plays a particular sound, for instance--will be included in the final score. I will also record the women’s voices and incorporate those recordings into the electronics, and I’ve invited them to choose some of their individual text responses to the subject matter that can become part of the background info surrounding this piece. [Two of these texts are quoted above.]

Q: Any final words on this collaboration or your work in general?

A: I’d just like to thank the women I’ve worked with at IWP for their insights into Juana’s story, and the education program at IWP for approving and facilitating this project.

Interview with Katie Young: Piecing Her Together

Interview: Murat Çolak's SWAN

In February of 2017, Ensemble Dal Niente premiered Swan, a sprawling piece for seven musicians and electronics. Here, composer Murat Çolak takes us behind the scenes.

Dal Niente Summer Camp

Musicians in Taxis Not Getting Coffee

By Andrew Nogal, Oboist

Now that I’ve slept for approximately 48 hours straight and washed six loads of all-black laundry – the staple of the freelance musician’s wardrobe – I am ready and eager to reflect on the Ear Taxi Festival, no doubt the boldest and most daring musical project I have watched unfold during my many years as a musician in Chicago. From my unusual perspective, Ear Taxi was a triumph of both imagination and execution. While I didn’t get to experience any Ear Taxi events purely as an audience member, I can offer a behind-the-scenes look at my preparation as well as a firsthand account of the convivial backstage vibe.

I performed not only on Dal Niente’s Friday night set, but also on Sunday afternoon as soloist with DePaul’s Ensemble 20+ (conducted by our own Michael Lewanski) and with the CSO’s MusicNOW Ensemble on Monday evening. In the week leading up to the festival, I had several twelve-hour workdays, during which I squeezed two or three rehearsals into days already packed with my usual teaching commitments, practice schedule, and reed-making routine. (I don’t drive a car, and I am grateful to the CTA and Metra for delivering me to almost every engagement on time!)

Months in advance, I knew that Ear Taxi would push me to my emotional and physical limits, and so I made the drastic, uncharacteristic decision to limit my caffeine intake during the festival. If you know me well, you know that this is a big deal. It was in Darmstadt in 2012 that I transformed into the kind of person who drinks coffee at all hours of day and night, and since then, my life has been an avant-garde pinball machine: I drink coffee, I bounce off the walls, I play the oboe. Ding ding ding, new high score! I couldn’t afford to have my nerves or health fail me during Ear Taxi, though, and I trusted that the music-making would be invigorating enough. A tiny cup of coffee at breakfast would be my only caffeinated ballast for about ten days, withdrawal headaches be damned.

That turned out to be a really good decision, because I was right: Ear Taxi enveloped me in positive, productive musical energy of a kind I certainly haven’t felt since I was a student. I was inspired to perform well not just for myself, but on behalf of the entire creative community of which I am a proud and active part. We were given a big, resonant stage on which to stand in front of a large, curious audience. It’s unfortunately rare as a performer of contemporary music to “get presented,” i.e., to have much of the unglamorous but essential legwork of concert production (fundraising, marketing, schlepping chairs and stands, transporting gear, selling tickets) offloaded from us musicians. Festival curators Augusta Read Thomas and Stephen Burns, festival manager Reba Cafarelli, and their whole staff and volunteer team are to be commended for following through on such a comprehensive vision of what this festival could be. Thanks to the host venues, too, for providing exceptional and comfortable spaces in which to work intensely.

And what about the music? It would be impossible to make any sweeping generalization about the programs or artists showcased at the festival. Two possible (among infinite) takeaways from the festival’s programming are that today’s composers and performers are exceedingly willing and able to engage thoughtfully with the music of the past and, secondly, that hostilities have perhaps softened between composers formerly seen as representing rival schools.

Personally, I thought that a lovely classicist thread tied together Ensemble 20+’s two selections: the Oboe Concertino by Bernard Rands set me up as a rhapsodizing protagonist backed up by the band from Ravel’s Introduction and Allegro. Next on the program, Eliza Brown’s watery, whispery A Soundwalk with Resi conjured the spirit of Richard Strauss.

On Monday night, Katie Young’s new piece where the moss glows received its world premiere at the festival’s finale, which doubled as the first CSO MusicNOW concert of this season. It stands to reason that the Chicago Symphony’s average concertgoer has probably never engaged with a piece like this – gnarly and knotted and whirring – performed live before. Dal Niente’s guitarist Jesse Langen described it with his usual aplomb: “maybe you’re somewhere in Portugal with a radio that’s 150 years old with these gigantic tubes coming out the back, and you tune in a faint signal from Dresden and it’s Wozzeck… that’s what this piece sounds like.”

Over the course of the festival, I overheard composers of what we’d generally call post-minimal music praising compositions that might get slammed elsewhere for being inaccessible or academic. It turns out that different listeners bring different life experiences to their seats in the concert hall, and those are hardly ever cut and dried; sounds that one person drably brushes off as “academic” might remind someone else of beats blasting at a warehouse rave. (Yes, I heard these two differing reactions to the exact same piece).

If you attended many of the concerts at Ear Taxi, first of all, thank you for being there, and second, I hope you weren’t expecting to love or connect with everything you heard! Even as a performer, I’m not crazy about all the music I play. Maybe that sounds controversial or surprising, but I believe it’s just a natural part of the great privileges and responsibilities of doing my job. It’s a meaningful and important challenge to try to give new music its best possible first (and second and third) performance. I cared so much about my concerts at Ear Taxi, I was willing to give up coffee for them.